On the day of Gilberto Mora’s debut (Tuxtla Gutiérrez, 2008), two things happened that people will remember. First, Mora was only 15 years old and took the field as the third youngest debutant in Liga MX history. Second, with his assist to Jaime Álvarez in the final moments of the match, he made history again by becoming the youngest player ever to register an assist in the competition.

Admitting my disbelief and lack of prior knowledge of the situation I am recounting, I prefer to focus on the fact that Mora debuted wearing the number 251. Upon looking into it, I discovered that youth academy players in clubs are often assigned very high numbers to differentiate them from the senior team players who already have squad numbers assigned for potential debuts.

A little over a year ago...

...Gilberto Mora played his first minutes with Club Tijuana, in the capital of the state of Baja California, just a step away from the United States. Far from his birthplace in Chiapas, in southern Mexico near the Guatemalan border.

Short in stature (1.68 meters) and slim body, still very much a boy, Mora has been climbing the ranks rapidly. Twelve days after his debut, he scored his first goal in the league—a record, by the way. Mora also became the youngest goalscorer in Liga MX history.

In that season, the 2024 Apertura, the Mexican midfielder would end up playing 826 minutes, 39% of the total available. The Apertura was followed by the 2025 Clausura (in Mexico, the Clausura is the first tournament of the year and the Apertura the second), in which Mora played 54% of the minutes.

The next major milestone in the short but meteoric career of this right-footed offensive interior or attacking midfielder, who often starts from the left side, was his call-up to the Mexican national team.

Mora was selected to play in the Gold Cup this past summer. Although he did not see minutes in the group stage, he was a starter in the semifinals, and his assist set up Raúl Jiménez’s winning goal, sending El Tri to the final. Mexico won its 13th Gold Cup, and Mora became the youngest player to ever win the tournament at 16 years and 265 days old.

A few months later, he scored his first goals in international club competition, netting twice against Los Angeles Galaxy in the Leagues Cup.

Right now...

...I would describe him as an exceptional conductor of attacks, already generating a gravity around him that draws opponents in, who lose track of the game as they focus on Mora. Gil Mora, as he is now known in Mexico, is one of the purest talents to emerge from the tricolor nation in recent times.

Recently, the Mexican has paired with Kevin Castañeda in the two-man forward 4-4-2 under Loco Abreu at Tijuana, but Mora always positions himself slightly deeper to connect with the central midfield duo and the left midfielder. Castañeda is a more traditional target forward.

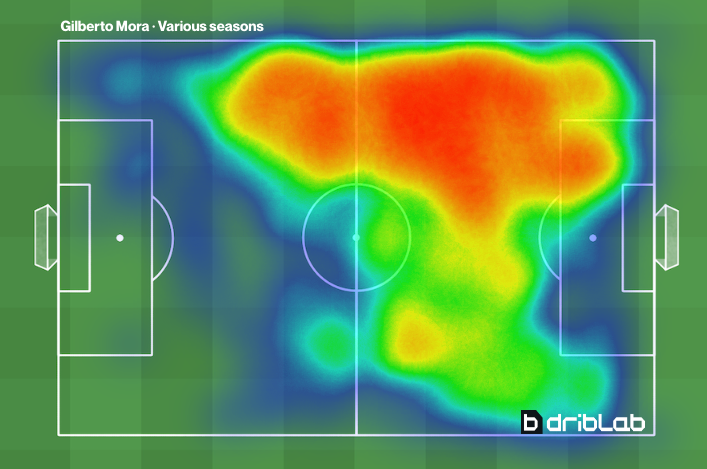

His heatmap outlines Mora’s profile: a right-footed, intelligent player who links up on the left side and can see the game in front of him, selecting passes to build the attack at his own pace. Yet Mora is not someone who relies on continuous touches. He participates less than similar players in his position (he ranks sixth among midfielders for the fewest passes per game in the Apertura so far). This stat, of course, is influenced by his team’s style.

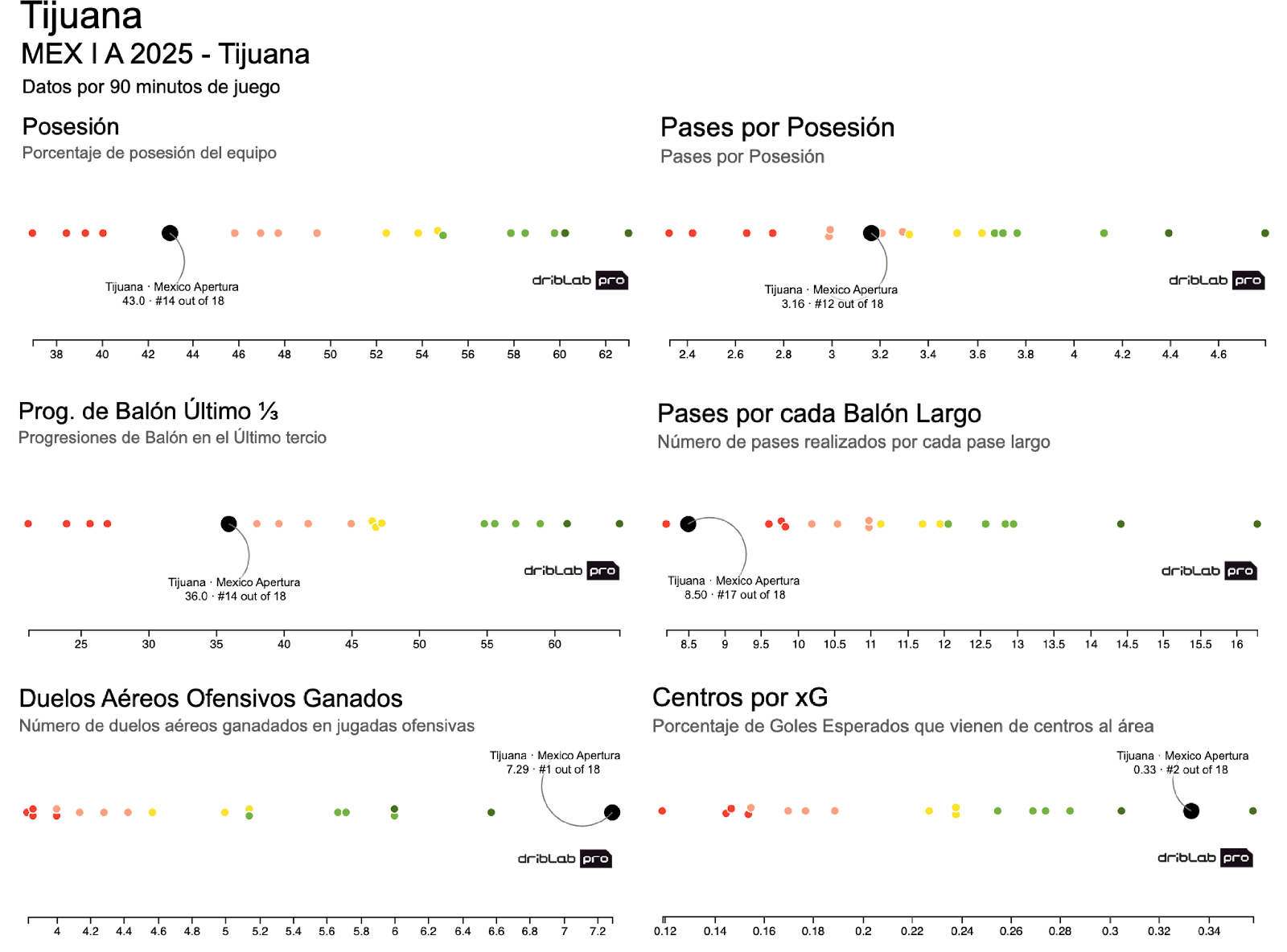

Only four teams have less possession than Tijuana in Liga MX. When the Xolos do have the ball, they do not show complex patterns, and the team rarely plays through Mora’s preferred zones. Only four of 18 teams average fewer ball progressions in the final third (every time a player advances the ball ten meters or more via carry or pass). In fact, Tijuana’s main way of creating threat is crossing the ball to the area, which generates 33% of their expected goals per game. Mora, at 1.68 meters tall, is clearly not the most favored player in this setup.

His lack of consistency is also dictated by his youth. It is common for very young players to struggle to consistently influence the game. That is normal.

Despite this, Mora already shows up with the punctuality of a top-level in key moments. In Tijuana’s last 10 goals (excluding penalties), the Mexican has directly contributed to 5, whether by scoring, assisting, or pre-assisting.

In this goal against Necaxa, we see Mora receiving the ball in his preferred zone, halfway between the central and left channels, from where he directs the attack.

Again: his football has gravity. He acts as a magnet for opponents, creating space, as seen in this play. Mora draws two defenders in, allowing his teammate to exploit the space created.

During this sequence, in which he carries the ball into the area, Mora uses a feint as the technical tool to create space. In the image below, he moves his right foot over the ball —without touching it— to sell the idea that he will go to his left. When the defender takes the bait and steps the wrong way toward the byline, the space between the opponents opens up, allowing Mora to make the pass.

Mora’s passing game...

...is fundamentally simple but super solid and intelligent, despite his inventiveness, technical skills, and creative solutions. Outside the areas where he can make a difference, he avoids risky passes. As noted, he is not a high-volume passer. In the past Clausura, only six midfielders surpassed his 89.3% passing accuracy.

Having frequently played in a two-forward setup while performing more like a central midfielder than a forward, we can compare him to the 47 forwards who played at least 450 minutes in the past Clausura. Mora would be the forward with the highest share of successful passes, and the best ball retention, at 91% (measured as the percentage of possessions not lost).

.png)

Our tool ‘Arrigo,’ which combines event data with tracking data, shows player performance both when applying pressure and when receiving it. In the Clausura radar, comparing Mora with other midfielders, we can see that he handles many high-pressure passing situations with exceptional accuracy.

Chamaco Mora completed more passes under strong pressure than 87% of midfielders in the Clausura. Only seven midfielders achieved higher accuracy than Mora (90.4%) in this kind of actions. In the areas where Mora receives the ball, defenders tend to apply close, aggressive pressure because these are truly dangerous zones. Yet Mora escapes with ease.

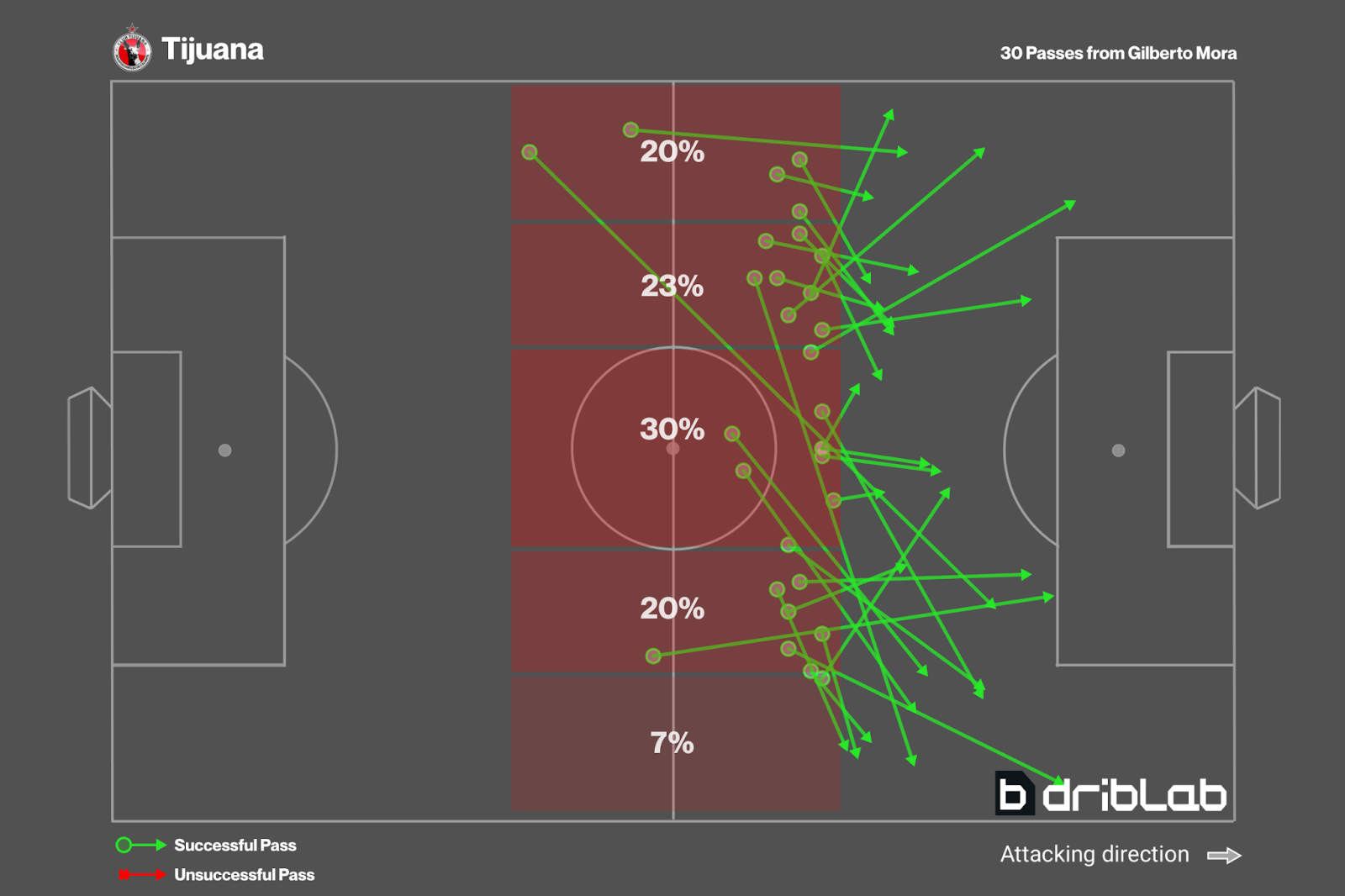

Once out of these high-pressure situations, the way he distributes passes reinforces my view of Mora as an excellent conductor of attacks: of his 28.3 passes per game, 13.7 reached a player in the final third. However, we value Mora mainly for his ability to move into space and pass the ball towards the final third without yet being in it. Of his 146 passes into the final third, 30 were launched from outside that area. A perfect linking thread.

One example is his goal against Pachuca—not for the finish, but for what he does before scoring. He receives the ball very deep, in the defensive third after a clearance, and his first thought is to start the attack.

He dribbles into his preferred zone and uses the outside of his foot to send his left-sided midfielder into the wide, free space.

The play continues as he occupies the spaces left by a shifting defense. Another positive aspect of Mora is that he never disconnects from the play. Sometimes this is because his pass is accompanied by a supporting movement to offer a combination option; other times, by staying engaged, he reaches shooting positions.

Mora interprets space brilliantly, with or without the ball. He senses movements around him, allowing us to highlight his greatest current strength: ball carrying.

It is his best skill...

...and main argument for top-level potential. In the last Clausura, 88% of midfielders did not surpass Mora’s 7.34 carries per game. He ranked 11th among midfielders in terms of volume, well above average. Yet quantity alone is not enough and we need to check whether those carries were effective and where they took place.

Mora’s carries are often positive. They aim to take his team closer to the goal. Of his 7.34 carries per game, 55% of them (i.e., 4.04) were progressive. At Driblab, we define a progressive carry as one that moves the team’s possession at least 20% closer to the opponent’s goal. Therefore, Mora manages to bring his team 20% closer to the opponent’s goal in almost 6 out of every 10 carries.

Questions arise due to his size. For such a small player, Mora’s dribbling effectiveness is remarkable. I believe this is due to three factors: a powerful initial burst, use of arms to fend off opponents, and his awareness of everything happening around him.

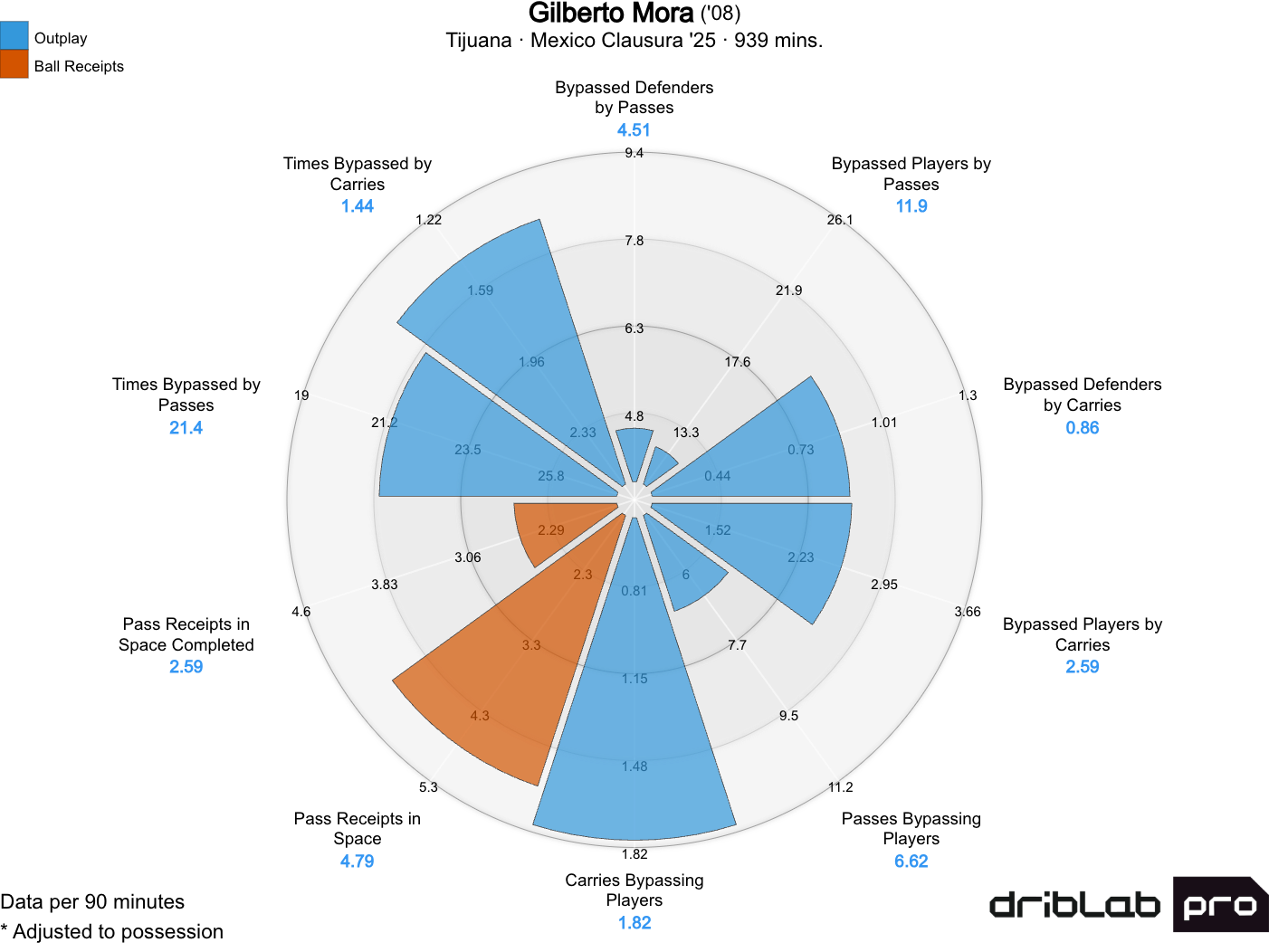

Using our ‘Arrigo’ tool, we can go further and see how Mora beats opponents. We discussed that his passing is safe, but his carries add unpredictability and danger. Only ten midfielders in the Clausura averaged more carries that bypassed players per game. Mora’s 24% of carries (1.82 per game) beat opposing players. On average, by carrying the ball he leaves 2.59 opponents behind per game, above the league mean.

Furthermore, our OutPlay radar highlights Mora’s ability to receive passes in space. His 4.79 passes received in space per game rank above 82% of midfielders in his league. At Driblab, we define passes received in space as those received in the opponent’s half with no defender within five meters toward goal.

In this clip, we see Mora find space to receive, feint backward to mislead opponents, accelerate with his first steps, look for a teammate on the right flank, and then slip through the opened gap as the defender shifts.

Gilberto Mora is one of the most promising football prospects Mexico has produced in the last decade. Despite the milestones and his immense potential, he is only 16. He still needs to grow physically and technically. But he is a talent that deserved to pass through the Driblab laboratory.