It may still be a metric that needs to be pushed further or may not be considered user-dominated, but Expected Threat (xT) can hold extraordinary information when used in the right way.

In this regard, we have found, from our own experience but mostly from the experience of clients or users, that ‘team’ metrics often shed crucial light on performance analysis. At the time, we made a widely shared content in which we visualised how to detect talent in teams that suffer, in which we activated ‘team’ metrics with the aim of knowing which players who do not stand out in general do so in a team with problems when the importance of a player is distributed by percentage. Something that arises as an opportunity to ask ourselves which player generates more threat for his team even if he is not the most important of them all. By modifying the premise we will find the dependency ratio of a team on this player and, therefore, an added value in the analysis of a player.

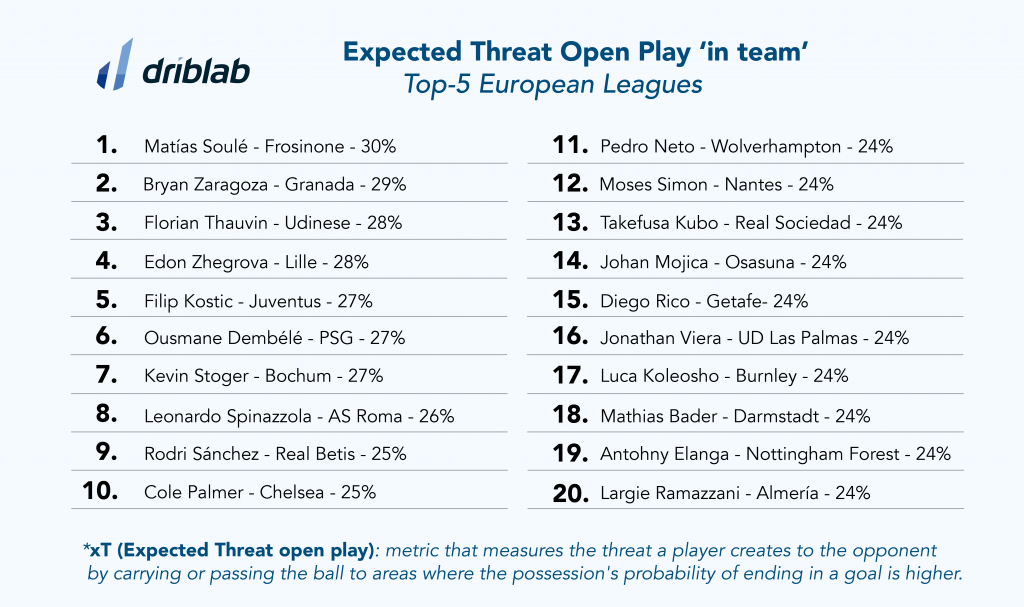

With the Expected Threat (xT) metric in team play we will find players in the five major leagues who generate the most threat in relation to all their teammates, discarding the total ranking. A brief reminder of what Expected Threat is: a metric that measures those actions in which a player carries the ball via a pass, dribble or dribble to areas of the pitch where the probability of scoring a goal is higher, excluding set pieces. The greater the distance between the origin of the play and the areas in or near the penalty area, the greater the value in the generation of threat.

With this metric we will recognise players from more modest teams who have an extraordinary importance in the generation of threat (dribbling, depth, passes into space, driving, crosses) as is the case of Matias Soulé, leading Frosinone in his year on loan, even standing out in absolute metrics, or Bryan Zaragoza, the revelation of Spanish football. The former generates 30% of his team’s threat while Bryan generates 29%.

We also find cases of much more important teams, especially because of the way they play. The case of Ousmane Dembélé explains the amount of metres he covers with dribbling and dribbling to start receiving near midfield and move the ball into the box, managing to invent quick attacks without connecting with other teammates. This metric is interesting because of the diversity of actions it encompasses and accumulates. Cases such as Johan Mojica or Diego Rico exemplify the profile of players with a good start and centre in teams with little possession or offensive volume. And this metric gives merit to the analysis.